Map helps Chinese man reunite with his family after decades

Since he was a child, Li Jingwei did not know his real name. He did not know where he was born, or for certain how old he was — until he found his biological family last month with the help of a long-remembered map.

Li was a victim of child trafficking. In 1989 when he was 4 years old, a bald neighbor lured him away by saying they would go look at cars, which were rare in rural villages.

That was the last time he saw his home, Li said. The neighbor took him behind a hill to a road where three bicycles and four other kidnappers were waiting. He cried, but they put him on a bike and rode away.

“I wanted to go home but they didn’t allow that,” Li said in an interview with The Associated Press. “Two hours later, I knew I wouldn’t be going back home and I must have met bad people.”

He remembers being taken on a train. Eventually he was sold to a family in another province, Henan.

“Because I was too young, only 4, and I hadn’t gone to school yet, I couldn’t remember anything, including the names” of his parents and hometown, he said.

Etched in his memory, however, was the landscape of his village in the southwestern city of Zhaotong, Yunnan province. He remembered the mountains, bamboo forest, a pond next his home — all the places he used to play.

After his abduction, Li said he drew maps of his village every day until he was 13 so he wouldn’t forget. Before he reached school age, he would draw them on the ground, and after entering school he drew them in notebooks. It became an obsession, he said.

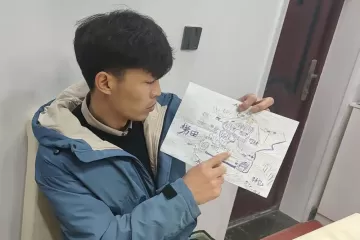

More than 30 years after his abduction, a meticulous drawing of his village landscape helped police locate it and track down his biological mother and siblings.

He was inspired to look for his biological family after two reunions made headlines last year. In July, a Chinese father, Guo Gangtang, was united with his son after searching for 24 years, and in December, Sun Haiyang was reunited with his kidnapped son after 14 years.

Reports of child abductions occur regularly in China, though how often they happen is unclear. The problem is aggravated by restrictions that until 2015 allowed most urban couples only one child.

Li decided to speak with his adoptive parents for clues and consulted DNA databases, but nothing turned up. Then he found volunteers who suggested he post a video of himself on Douyin, a social media platform, along with the map he drew from memory.

It took him only 10 minutes to redraw what he had drawn hundreds, perhaps thousands of times as a child, he said.

That post received tens of thousands of views. By then, Li said police had already narrowed down locations based on his DNA sample, and his hand-drawn map helped villagers identify a family.

Li finally connected with his mother over the telephone. She asked about a scar on his chin which she said was caused by a fall from a ladder.

“When she mentioned the scar, I knew it was her,” Li said.

Other details and recollections fell into place, and a DNA test confirmed his heritage. In an emotional reunion on New Year’s Day, he saw his mother for the first time since he was 4.

As Li walked toward her, he collapsed on the ground in emotion. Lifted up by his younger brother and sister, he finally hugged his mother.

Li choked up when speaking about his father, who has passed away. Now the father of two teenage children, Li said he will take his family to visit his father’s grave with all his aunts and uncles during Lunar New Year celebrations next month.

“It’s going to be a real big reunion,” he said. “I want to tell him that his son is back.”

During the first several months of the pandemic in the U.S., Dina Levy made her young daughter and son go on walks with her three times a day.

They kicked a soccer ball around at the nearby high school. The children, then 11 and 8, created an obstacle course out of chalk and the three timed each other running through it. They also ate all their meals together.

Levy is among scores of parents who indicated in a new survey from the U.S. Census Bureau that they spent more time eating, reading and playing with their children from March 2020 to June of 2020, when coronavirus-lockdowns were at their most intense, than they had in previous years.

“With school and work, you split up and go your own way for the day, but during coronavirus, we were a unit,” said Levy, an attorney who lives in New Jersey. “It really was, I don’t want to say worthwhile since this pandemic has been so awful for so many people, but there was a lot of value to us as a family.”

In a report on the survey released this week, the Census Bureau includes some caveats: A large number of people did not respond. Also, compared to previous years, more of the parents in this survey were older, foreign-born, married, educated and above the poverty level. The survey also does not measure the long-term impact of the pandemic, which is now entering its third calendar year, so it is unknown whether the increased time with the children has stuck.

The findings of the Survey of Income and Program Participation are based on interviews with one parent from 22,000 households during the first four months of the pandemic in the U.S. The survey found that the proportion of meals the so-called reference parents shared with their children increased from 84% to 85% from 2018 to 2020, and from 56% to 63% for the other parents.

Some parents also read to their kids more in 2020 compared to previous years, though there were variations based on income, education and other factors. In 2020, 69% of parents reported reading to young children five or more times per week compared with 65% in 2018, and 64% in 2019, the report said.

“Families knew before the pandemic that they were overstressed. Kids had so many places to be. Parents were juggling an awful lot,” Froma Walsh, co-director of the Chicago Center for Family Health at the University of Chicago, said in a phone interview. “The pandemic made people not go to work, and our kids were home. It really helped parents to say, ‘Hey, wait a minute. We are able to have real family time together that we weren’t before.’”

On the flip side, the report found that outings with children decreased for parents because of travel restrictions and lockdowns, dropping from 85% in 2018 and 87% in 2019 to 82% in 2020. The drop was starkest for solo parents, going from 86% in 2019 to 75% in 2020, according to the survey.

The pandemic also strained many families. The death of loved ones, job losses, financial worries, remote learning, social isolation, and the demands of child and elder care all took a heavy toll, Walsh said.

“The key point is families have experienced extreme stress and strain over the course of this prolonged pandemic,” Walsh said. She said her research shows that families do best when they share positive values, take a creative approach to problem-solving and have the flexibility to adapt.

“Those families that can pull together and practice resilience are doing well, and it actually strengthens their bonds,” she said.